Introduction

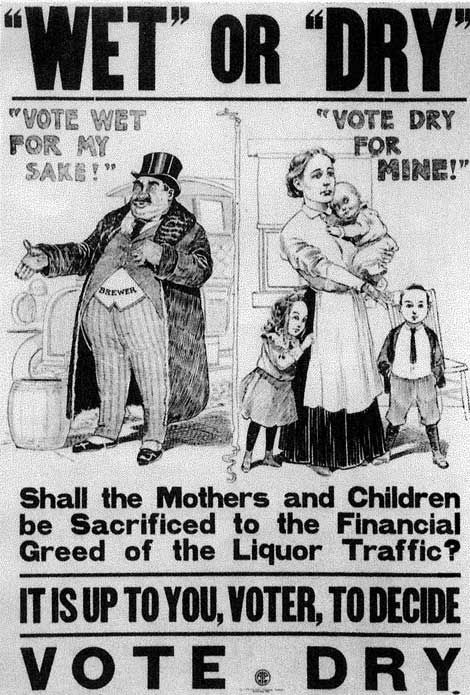

Before Prohibition was enacted, the temperance movement of the 19th and 20th centuries among other things pushed for the moderation of alcohol consumption. The movement attracted support from a large number of American women, women who for too long had been subject to the affects of alcohol on the men in their lives. The reputation of alcohol for many had taken the form of a menace that was to blame for problems in American society including homelessness, crime, violence, and a general deterioration of the country’s moral standards. Men were considered to be most at risk from the affects of alcohol, and considering that men of the time were charged with supporting the family it was thought that a man could literally drink his family into destitution.[1] While the movement’s original intention was to push for moral reform it became apparent that in order to effect lasting change they would need to focus their influence towards politics.

The Temperance movement saw its first statewide success in Main. The “Maine Law” as it was called passed in 1851 and prohibited the sale of alcohol except for mechanical, medicinal or manufacturing purposes.[2] The working class of Maine disagreed with this measure and on June 2, 1855 opposition turned violent. Known as the “Portland Rum Riot”, protesters broke into city hall looking for liquor that was thought to have been stock piled by the Mayor. Despite the reaction from the public the Maine Law would became a model for other states and by the year’s end twelve states had Temperance laws in affect.[3]

The Women’s Christian Temperance Union was founded in Cleveland Ohio in 1847 and its goal was “to create a "sober and pure world" by abstinence, purity, and evangelical Christianity”. Under the leadership of Annie Wittenmyer, an experienced wartime fund-raiser and social reformer the group constructed a constitution that called for the entire prohibition of the manufacturing and sale of intoxicating liquids.[4]

The group would eventually see a change in leadership when Frances Willard was elected as its president in 1879. Soon after, they became one of the largest and most influential women’s groups of the 19th century aligning with more than 1,000 chapters nationwide, as well internationally. Willard developed the slogan "Do Everything" for the WCTU, encouraging its membership to engage in a broad array of social reforms through lobbying, petitioning, preaching, publishing, and education. Her vision encompassed goals like raising the age of consent, labor reforms such as the eight-hour work day, prison reform, scientific temperance instruction, Christian socialism, and the global expansion of women's rights.[5] After Willard’s death in 1898 the group moved away from other issues to focus on prohibition of alcohol in the United States.

Another prominent organization that fought for prohibition was the Anti-Saloon League. After its founding in 1893, the league began to focus all of its energy on the issue of national prohibition, more importantly the league sought to influence the political scene. One of the league’s most effective tactics in the fight for nationwide prohibition was to apply pressure to all levels of government whether local, state, and federal.

On local levels chapter members worked with police to strip establishments of their alcohol licenses when they were caught breaking the law. At the state level the league worked to gain support of the prominent religious parties in hopes of swaying voters in local elections.[6] Another tactic used by the Anti-Saloon league was the spread of literature, and the American Issue Publishing company was created by the league to produce large quantities of pamphlets, magazines and books that were sent all across the country. The success of these tactics lead to the league becoming a powerful national organization that with the help of the WCTU saw the movement of national prohibition become a reality.

On January 16th, 1919 the 18th Amendment of the United States constitution was ratified. Its purpose was to prohibit the manufacture, sale, and transportation of intoxicating liquors. The defining language of this amendment came in the form of the National Prohibition Act, which oddly enough left the citizens right to consume alcohol untouched. At midnight on Jan 17, 1920 the National Prohibition Act better known as the Volstead Act went into effect.

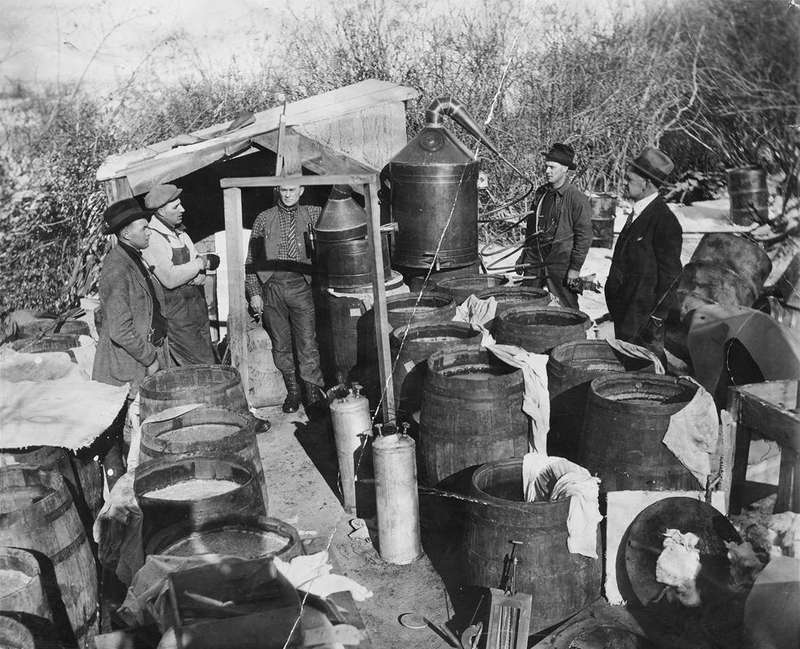

This Exhibit takes a look at some of the unintended consequences of the implementation of Prohibition in the United States. One such consequence that will be explored is the illegal production and distribution of alcohol otherwise known as “bootlegging”. The American public was no longer legally allowed to buy alcohol, and companies were no longer legally able to produce it unless for medical or scientific purposes, but that did not stop the efforts of American citizens to procure the illegal liquids. Smuggling booze into the country from Canada, Mexico, Cuba and the Bahamas was one of the earliest methods used, and it was effective, but the demand for alcohol within the U.S was too great to depend on one source. Soon the American people would take it upon themselves to make their own booze. Citizens who had never committed a crime in their lives took to building stills and brewing in their homes. Some turned kitchens, bathrooms, and backyards into liquor making operations, while others created places to enjoy their illegal drink. Pre-existing operations that were already operating would also be effected by the demand which led them to switch their focus from quality to quantity. The intent of Prohibition was to reform a morally wayward country, but as citizens were stripped of what they considered to be an American freedom the country began to witness an unprecedented swell of criminal activity.

Because the sale and transportation of booze were illegal, citizens had to come up with clever and even brazen ways to do business. Criminal minds of the time also sought to do business, and because they were accustomed to breaking the law, prohibition acted as a greenhouse for their criminal activity Alphonso Capone of Chicago would become the most notorious criminal of the time by constructing an illegal operation that produced, distributed, and sold alcohol to a thirsty American public.[7] His enterprise would be so successful that it would eventually begin to bring in 100 million dollars a year, but that money did not come easily.[8] Gangsters and police fought to the death for control of alcohol, and in many cases citizens who were once law abiding citizens would be caught in the middle.

The final unintended consequence that this exhibit will look at is the economical impact of prohibition. With the closure of breweries, wineries, and distilleries citizens would lose their jobs, and in many cases their only source of income. States would lose their main sources of income, and as their citizens lost wages local businesses lost their profits, and eventually their ability to stay in business. Money that was once taxable would soon be dealt on the black market, and state and federal agencies would lose millions in the process.

[1] Dobyns, Fletcher. The Amazing Story of Repeal : An Exposé of the Power of Propaganda. Chicago, Ill. New York: Willett, Clark &, 1940.

[2] The Sedley Family ; Or, The Effect of the Maine Liquor Law. Boston: T.O. Walker, 1853.

[3] Pegram, Thomas R. Battling Demon Rum : The Struggle for a Dry America, 1800-1933. The American Ways Series. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1998.

[4] Gusfield, Joseph. "SOCIAL STRUCTURE AND MORAL REFORM; A STUDY OF THE WOMEN'S CHRISTIAN TEMPERANCE UNION." American Journal of Sociology61, no. 3 (1955): 221-32.

[5] Cott, Nancy F. History of Women in the United States : Historical Articles on Women's Lives and Activities. Munich ; New York: K.G. Saur, 1992.

[6] Odegard, Peter H. Pressure Politics, the Story of the Anti-saloon League. New York: Columbia University, 1928.

[7] McGill, Sara Ann. Al Capone. Place of Publication Not Identified: Great Neck Publishing, 2005.

[8] Pasley, Fred D. Al Capone : The Biography of a Self-made Man. A Star Book. Place of Publication Not Identified]: Kessinger Pub., 2012.